This article is part of the series Communication and Media Policy

With this series dedicated to Communication and Media Policy, journal Temas’ blog Catalejo suggests for discussion a number of problems about the existing media model and other general social communication-related issues. The series focuses on several topics of interest not only to professional journalists but also to a political agenda drawn up since January 2012 and offered for public debate in the last few years. These topics are as follows:

Is there a universally accepted model of communication policy or do the different countries or regions have their own? Could one of those models be more suitable, useful or viable to Cuba?

How can Cuba’s true public sphere be characterized regarding the access to information, the media, and freedom of speech? Which practices are—or not—progressive? How to distinguish public from state media in Cuba? And from the non-state media? What requirements must a communication system meet under a new socialism?

To what extent do the regulations currently in force respond to the needs of that new communication system? What are its achievements and shortcomings? What are the benefits and costs of postponing the discussion of these issues until the 2023-2028 legislative calendar through a Communications Act? What concepts and practices should anticipate the said Act and start to change our political culture of communication?

For Jose Marti, the idea of a press that is answerable to the people and their opinions would require as indispensable elements the study of the needs of the country, the consensual establishment of its improvements and the facilitation of the administrative work that governs it. This view also holds the foundation of a second requirement: to contribute with one’s work to the ratification of the political system in which it is practiced.

These premises become particularly important in a Cuba that is updating itself, growing, connecting to the internet and renovating its socio-economic model, for all of which the press needs to reaffirm itself like a mirror, an enterprise and a platform in dialogue with its society. This new context demands its media to have better efficacy and coherence with the new logics of information access and distribution. It becomes vital to renew management formats to promote their public nature and exercise a journalism capable of offering timely news, of connecting the political and the public environments.

One of the main researchers on the Cuban press, Julio García Luis (2013), argues that the social characteristics of the press are not by themselves sufficient guarantee of a press that is a public service, participative, supported by values and able to form them—a process which needs to differentiate between its ownership and the ways in which it is managed.

In conjunction with this difference, many debates within the profession affirm that being state-owned does not by itself determine either their public character or their communicative qualities, which would allow for fulfilling their mission as a public service. It is a question of finding the proper mechanisms in editorial and economic management, to validate and apply them.

The public service press: from ideal to practice

According to some of the foremost researchers of the public media (Garnham 1990), in order to fulfill their role, the media must encourage a more egalitarian diffusion of symbolic exchanges, founded in their superiority, to offer all citizens—in any geographic area—an equal possibility of access to a wide range of entertainment, information and high-level education, as well as the capacity of the provider to satisfy the varied preferences of the users—and not only of those who offer the greatest benefits.

In order to articulate these intentions, a set of common attributes can be identified (Becerra & Waisbord 2015): editorial and financial autonomy; a broad range of services—not only in geographic or socio-economic terms but also in the different languages generated by the technological concurrence—; plurality and diversity in content and information; that it should be ruled by the public interest and not by commercial standards or party expectations and, finally, accountability to the people and to other regulatory entities having autonomous leeway with respect to the government.

In order to be confirmed as a public service, the media must convert their public in protagonists of the control processes and the establishment of agendas; situate themselves at the centre of the democratic life of the country; and act as the pillar of the dialogic communication, of the debate, the diversity of ideas and the construction of identities. Their role is to inform, educate and also entertain the citizens, for which they will require a guarantee of editorial autonomy, appropriate financing and transparency. The adaptation to the new technologies and the continuous professional improvement of the journalists are fundamental requirements for their satisfactory performance.

According to Pascual Serrano from Spain (personal communication, February of 2018), realizing the task of developing a model of the media as a public service depends on the governments, and on how well they understand the right of citizens to inform and be informed, as being the mission of a social state—the same way in which it must guarantee health or education. In order to achieve this, citizens and professionals must reclaim it and fight for its existence and progress.

The public service press entails a challenge, as expressed in the dichotomy of meanings proposed by Thompson, expressed on the one hand in the domain of institutionalized political power under the control of the sovereign State, of the economic activities and personal relations domains, on the other, where the “public” is defined as open and available, and the “private” as hidden. The dichotomy between public and private does not refer only to concepts of property, but also in frankness vs secretiveness, visibility vs invisibility (Thompson 1998, p. 168). So the public media must bring to the people the information they require and incorporate them in the process, so that they can analyze every conflict from all perspectives, so they can validate the political system by questioning, over and over again, its forms of doing things, and oblige it to perfect itself for the common good. In the end it is a question of achieving a public service press, and not just a handful of public media.

Probably because of the complexity of what has just been described, there are not many practical and concrete examples of this ideal. Different perspectives and theories have been offered in the past, from the United States to the Soviet Union, passing through all of Europe, and they have been debated, stated in the simplest way, as being between a commercial press and a governmental one.

One of the reasons that the public press has been rejected without serious analysis is because it has been seen as a modality that is totally governmental, without freedom and, therefore, with a lower journalistic quality. The key seems to be that the public press should respond to public interests, those of the citizens, of society—which are the interests owed to the State in a democratic political system. It should not be subordinated to the individual interests of those people who have power.

One subtle change introduced in Europe after the Second World War as part of the Social Responsibility theory put an alternative option on the table, still imperfect, but with hopeful features regarding the constitution of a press as public service. If in the United States the media continued being mostly private, and the principles of social responsibility had to be achieved through an almost idyllic self-regulation, in Europe the State maintained, or amplified, its role of owner and transmitter of a fairly large number of media with the idea of public service, and in particular the broadcasting media.

In parallel they created a series of institutions and mechanisms that limited state influence over the media and insured constant accountability to society. This resulted in the creation of the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) in Europe which, over time, evolved into the Public Service Media (PMS), which has been widely studied.

If its realization in practice has been more or less effective in achieving its principles in certain contexts and phases—though it has not escaped criticism—the European public press stands out for its sustained efforts to maintain high levels of professionalism and autonomy, directed towards placing the public’s interests on its agenda. Its study could contribute some workable models to the updating of the press in Cuba.

Cuba: What press for what socialism?

In her doctoral research, based on a crossover of cases studies of the General Meetings of UPEC [Union of Cuban Journalists] prior to the IX Congress of the organization, and of a series of focal groups, journalist Rosa Miriam Elizalde revealed the loss of credibility and trust in the sector, the competence of the hegemonic cultural and information industry, the demoralization, low self-esteem, ethical injuries suffered by journalists and the low representation of the citizens’ agenda, as conflicts associated with the social stability of the Social Communication System in Cuba, particularly in the mass-communication media (Elizalde 2014, p. 42).

During the IX Congress of UPEC, Raul Garcés, in his “7 theses on the Cuban press” signalled its low capacity to treat the country’s reality in a critical and interpretative manner: “for whatever reasons, we have constructed a model of reality that opposes the so-called external hell to the supposed domestic paradise. We have frequently replaced judicious reasoning with propaganda, data with interpretation, events with news, the story with the adjective, the wealth of the processes with the absurd synthesis of its results” (Garcés 2013).

Meanwhile, the political documents that guide the current process of change define information, communication and knowledge as public goods, and civic rights “that are exercised responsibly, preserving technological sovereignty, with observance of the established legislation in matters of national defense and security” (PCC, 2017). The process of Updating the social and economic model does not only imply an opportunity for the renewal of the press; it is also a requirement. A socialism that is being renewed needs a new press.

Based on the idea that looking outward does not mean copying, and bridging the gap between the respective political, social and economic contexts, the set of traits that characterize the European public service press is useful to assist in our thinking of what we can and cannot do in the future of the press in Cuba.

From this starting point, in my investigation of 2018 I defined some factors in the workings of the public media in Europe, and tried to establish levels of correspondence between the experiences mentioned and the Cuban context. By means of surveys and group discussions, I submitted some of the forms and functional mechanisms mentioned to the appraisal of professionals in order to determine their levels of viability and feasibility. [i]

Autonomy, accessibility, diversity, identity, representativeness, debate, investigation, loyalty to truth, education and innovation—these were some of the main characteristics in the type of press that was used as model. In the European context, the media of this type articulate various strategies related to regulation, financing, participation of the public, adaptation to technology, and development of human resources.

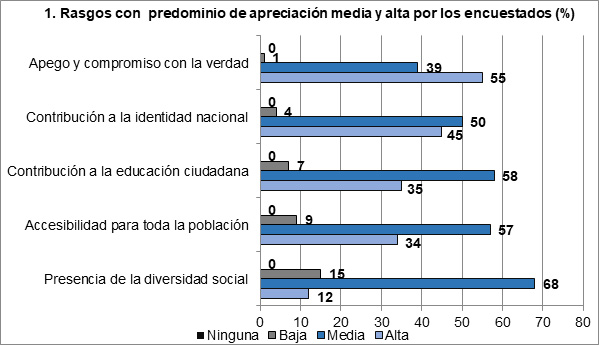

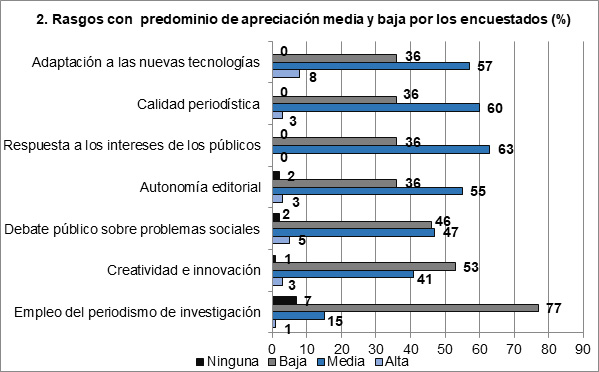

Using the information provided by those surveyed, Graphs 1 and 2 show a portrait of the current Cuban model, according to the twelve general characteristics we outlined as being distinctive of the public service press. As well, they present the percentages by which the values of high, medium, low or none were assigned to each of the characteristics, according to their presence in the Cuban press now.

Although all characteristics obtained a majority of votes for the medium option, we can distinguish two groups: one in which the evaluations are situated between medium and high (Graph 1), and another in which they are situated between medium and low (Graph 2).

Source: Personal elaboration by the author, based on the results of the Survey.

It can be seen that the qualities of loyalty to truth, contribution to national identity, civic education, accessibility, and the presence of social diversity lean towards higher evaluations on the part of those surveyed. This represents a first important step, because ultimately, these are the starting points that can assure the practice of journalism as a public service.

On the other hand, those traits more related to practices and concrete qualities like editorial autonomy, the use of investigation, journalistic quality, adaptation to technologies, innovation, debate on social problems and response to the public interests, all—with their nuances—lean towards the lower option.

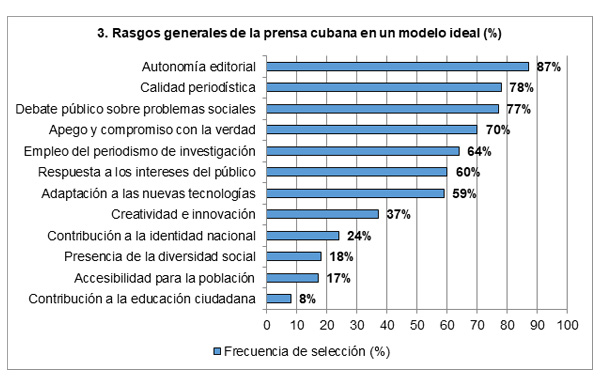

Other interesting data were those contributed by the responses to the question as to which of these traits have the highest importance in the production of an ideal model for the country. In accordance with these, a chart of the fundamental requirements of the Cuban press could not omit key words like honesty, autonomy, quality, debate, investigation, technological adaptation, and public interest. Graph 3 shows the traits that were most marked by those surveyed, based on the six main traits selected for the construction of this ideal model.

Graph 3: General traits of an ideal model of the Cuban press (%)

Source: Personal elaboration by the author, based on the results of the Survey.

With the exception of loyalty and commitment to the truth, which is again located among the most valued traits and correspond to the principle of honesty that the Cuban press defends—those surveyed indicated the most important elements that they had previously qualified mainly as medium to low when evaluating the workings of the current model. This was the case with editorial autonomy, journalistic quality, public debate, investigative journalism, response to public interest and technological adaptation. The professionals who were questioned see these traits as fundamental challenges in the construction of an ideal press in the Cuban context.

All professionals surveyed considered it important that the public should be able to participate in setting up the agendas and programs of the press. They argued that this is “inherent in the social function of the media on the Island”, as the public definitely constitutes their reason for being and their main purpose; only in that way will their concerns and discussions be placed on the national debate agendas. Moreover, they also insisted that “by means of this participation the quality of journalism will be strengthened,” as well as “loyalty to the truth,” and “the link to the frame of reference.”

How can the change be accomplished?

The updating of the press in Cuba is closely related to the ways in which all communication media should be managed, editorially and financially. Another requirement is the identification of the specific mechanisms and tools needed for these processes, and to validate them in the Cuban context.

When one mentions the public service press in the European context—even from the perspective of discourse and theories—the defining trait that stands out is editorial independence as related to the political and economic powers. The experience of a commercial press practice on the one hand, and an unstable multiparty political system on the other, generated the perception that in order to achieve an ideal press, it is necessary to slow down influences of all types in editorial policies. Journalism, it is argued, must be neutral, objective, impartial. Such a description, of course, is idyllic—as recognized voices from the European press admit today.

To replicate this extreme perspective in the Cuban context would be equivalent to not recognize a different political and social reality. One of the fundamental functions of the press in Cuba has been to validate and participate in the construction of the revolutionary process. To practice journalism in a socialist country entails specific challenges in addition to those common to all communication media in any place in the world. The key is finding the balancing point.

The Cuban solution should start with recognizing the media as being part of a political process that has brought us to where we are now and from which we cannot separate in order to achieve “absolute and objective independence.” At the same time, it is a question of betting on the political, professional and intellectual capacity of the protagonists who, from within the media, also construct society, and who, throughout many different circumstances, have demonstrated the ability to do so. It is a question of renewing and adapting to our Island the European experiences related to these issues of the public service press: editorial autonomy, not political independence; honesty and ethical engagement, not impartiality or neutrality.

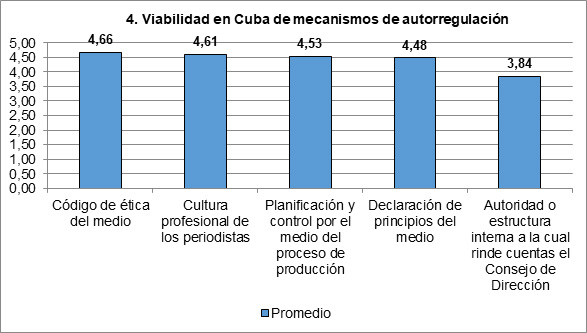

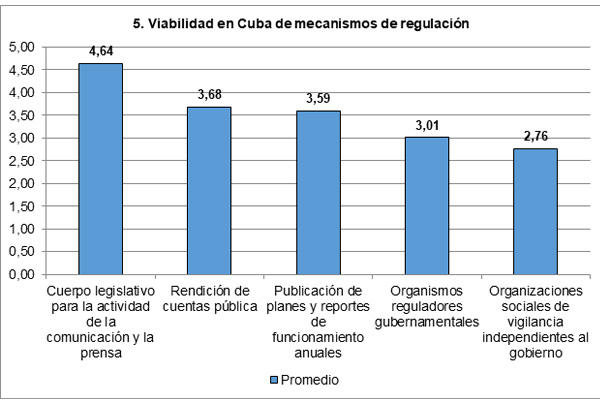

So, this point of equilibrium between the relation with the political powers and the need for editorial autonomy must be defined and controlled through regulatory standards and mechanisms. The following graphs show the averages of those surveyed when asked to rank from 1 to 5 the levels of viability in Cuba of some of the European experiences related to self-regulation (Graph 4) and regulation (Graph 5).

Graph 4: Viability in Cuba of mechanisms of self-regulation

Graph 5: Viability in Cuba of regulatory mechanisms

Source: Personal elaboration by the author, based on the results of the Survey.

The graphs show that the professionals surveyed favor self-regulation mechanisms, which they call a responsible practice, exercised and controlled from inside the media, above those who established the regulations.

And as far as the latter are concerned, only the one that referred to the existence of a body of legislation for the practice of communication and press obtained an average (4.64) similar to that of the self-regulatory traits. The social organizations of surveillance obtained the lowest average (2.76), which may indicate a lack of knowledge or a low viability of this element in the national media. The governmental regulatory institutions reached a medium average (3.1), probably because the professionals realize their possible viability, but do not consider them to be the most important, or because they recognize possible hitches or difficulties to their implementation.

A separate mention should be made of the European experiences regarding the accountability process and transparency of the operations. Although this has not been frequent in the professional practice of Cuban journalism up to now, the averages of feasibility reached in the outcome of the survey (3.68 in the first and 3.59 in the second) show that they could be other mechanisms to be taken into account when the time comes to organize the regulatory processes of the national press.

Concomitant with what Graphs 4 and 5 show, the group discussion on the practical application of the principle of autonomy was mainly directed towards the need for a legislative body which would establish and control the workings of the press and communication of the country and, above all, towards the importance of favoring—over and above the regulations—the self-regulatory mechanisms and the professional culture of the journalists, as reflected in the planning and production processes that take into account the public interest.

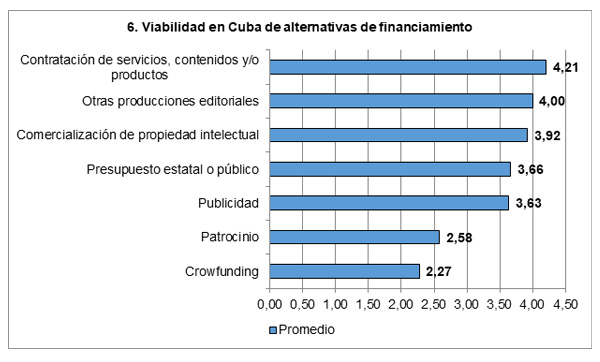

At the same time, a restraint identified in the model of the current Cuban press is the excessive centralization of the economic management in institutions outside the media. Questioned regarding the possible alternatives for financing, those surveyed validated the possibility of integrating other mechanisms with the government budget to generate income. Graph 6 shows the averages of the responses of the professionals asked to evaluate between 1 and 5 the levels of viability in Cuba of some of these types of options applied in the public press in Europe.

Graph 6: Viability in Cuba of alternative financing

Source: Personal elaboration by the author, based on the results of the Survey.

More viability was given to self-financing options closer to the traditional operational methods, which in some cases have already been tried. On the other hand, the options of sponsorship (2.58) and crowdfunding (2.27)—mechanisms farther from the Island’s context—obtained lower averages.

An element to note is the medium average obtained by advertising (3.63), in spite of the fact that in recent discussions by the Union this has been one of the most valued alternatives. This result could be attributed to the fact that Cuban journalists still look askance at a practice which has singled out especially the commercial press and which, on many occasions, has ended up compromising the editorial policies of the media. In fact, in Europe the public service press tends to limit its use; and a practice of this type in our country should be established with its own regulatory mechanisms.

As far as the governmental subsidy is concerned, the average validation level this obtained in the survey results could denote that any financing should include other sources. An itemized analysis of the responses received shows that although the average validation among journalists was 3.44, among managers it was 4.40, which makes it the most valued option within this subgroup. The difference between them could indicate a perception among the managers that there is a greater risk associated with up or reducing the governmental subsidy.

Concomitant with these evaluations, the majority of the discussion group agreed on possible alternatives for the organization of a new economic system, which would combine the governmental budget with other sources of financing and which would especially recognize the capacity of directors and internal staff of the media to manage it. This renovation of financing mechanisms will require higher levels of preparation and education on the part of managers and journalists.

To achieve an effective organization of the public media, the renovation of the Cuban press model will also require boosting management capabilities in the field of new technologies and, above all, innovation and creativity in a dynamic context of media convergence. The study identified great shortcomings in the processes of economic management that would sustain this development, and the necessity—starting in the media— to understand and apply the potentialities and challenges implied by the new technologies and media reality.

Some practices that raise interest are the use of innovative hypermedia and multimedia resources in the content development. In this area, and among other features, journalists advocate for a greater use of infographics, illustrations, videos, audios, maps and interactive graphics, which allow the dissemination of news in a more complete and attractive manner. Moreover, the current management of social networks, the creation of apps for mobiles and the production of podcasts or blogs related to the media, are also alternatives that can be developed.

The reconfiguration of the workforces and tasks in editorial offices, and the association with universities, institutions, enterprises and other spheres in order to generate alliances that would improve the quality and scope of the newspaper production were also options valued in the investigation.

The guild also values continuous retraining, which allows journalists and other professionals to stay up-to-date regarding technological changes in order to deal effectively with new options. Among the resources that would strengthen this task, importance was given to the possibility of professional improvement from within the media, to the association with universities and other institutions, taking advantage of courses and training related to the traits and needs proper to each media, to the function of the UPEC leadership, to the introduction of mechanisms of salary supplements based on retraining, as well as some formal requirements relating to contracts and legislation.

In conclusion, the capacity of the Cuban press to function as a public service and to be validated as an ideal alternative will depend on its ability to make more effective the participation of the users in setting up media agendas and programs.

Cuban journalism needs to pulsate with and reflect the concerns of the nation, to generate a serious and profound collective debate, in order to identify through feedback, causes, contexts and possible solutions. It should contribute, therefore, to the formation of a citizenry that will take the role of protagonist, indispensable for Updating the Model and the redefinitions of socialism. Only to the extent to which it fulfills such missions will it become a true guardian of the public trust.

______________

[i] The survey was distributed to 92 professionals of the Cuban press, of both genders, among whom were 47 journalists, 28 managers, 9 professors, 5 directors of UPEC and 3 other newspaper persons who were then working outside the media. The group included different age ranges and the five journalistic expressions (printed press, radio, television, digital media and news agencies).

Deje un comentario